The aggressive push to divert ancestral lands of the Nicobarese people for the Great Nicobar Island mega-infrastructure project—particularly the proposed transshipment port and associated developments—is not merely ethically troubling; it is fundamentally illegal under Indian law.

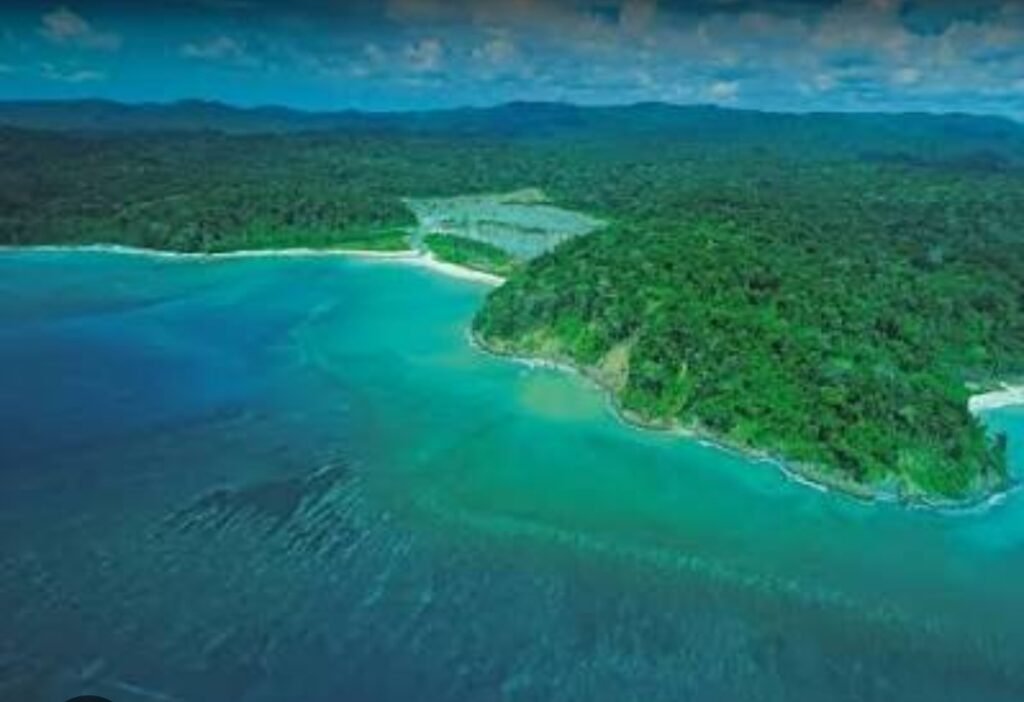

The recent allegations by the Nicobar Tribal Council that district administration officials are pressuring them to sign “surrender certificates” for pre-2004 tsunami village sites in areas like Galathea Bay, Pemmaya Bay, and Nanjappa Bay expose a pattern of coercion that directly contravenes key protections enshrined in statutes like the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006, and related constitutional provisions for tribal autonomy.

At the heart of the illegality lies the Forest Rights Act, 2006, a landmark legislation designed to correct historical injustices against forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest dwellers.

The FRA mandates the recognition and vesting of individual and community rights over forest lands before any diversion for non-forest purposes can occur.

Critically, it requires free, prior, and informed consent from affected Gram Sabhas (or equivalent bodies like the Tribal Council in these islands) for projects involving forest diversion. Diversion without settling these rights and obtaining genuine consent is unlawful.In the case of the Great Nicobar project, which seeks to divert around 13,000 hectares of forest land (including parts of tribal reserves), the Andaman and Nicobar Islands administration has repeatedly claimed that FRA rights were identified and settled as far back as 2022.

This assertion enabled the grant of Stage-I forest clearance. Yet the Nicobar Tribal Council—the apex body representing the Nicobarese Scheduled Tribe—has categorically refuted this, stating in formal complaints (including to Union Tribal Affairs Minister Jual Oram in August 2025) that no FRA processes have even been initiated, let alone completed.

No individual or community forest rights certificates have been issued to the Nicobarese for these ancestral lands.If rights remain unsettled, any diversion is premature and illegal.

The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has itself acknowledged that compliance with Stage-I clearance conditions—including full FRA settlement—remains pending, blocking final approval. Pressuring the Tribal Council to sign vague “surrender certificates” (with templates circulated via WhatsApp and offers to draft them) circumvents the FRA’s consent mechanism.

It attempts to manufacture post-facto “agreement” through coercion, rather than genuine Gram Sabha-level consultation. Such tactics violate the spirit and letter of the Act, which prohibits forced relinquishment of rights and demands transparency and voluntary participation.

Compounding this are protections under the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956, which safeguards tribal reserves and restricts non-tribal interference in designated areas.

The project’s requirement to de-notify parts of these reserves (170 sq km in total, with earlier NOC withdrawals by the Council) further undermines this framework when done without full tribal endorsement.

While the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA)—which empowers Gram Sabhas in Scheduled Areas—has limited direct application in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands due to their unique administrative setup (governed by Presidential Regulations like the A&N Islands (Panchayats) Regulation, 1994, and A&N Islands (Tribal Councils) Regulation, 2009), the underlying principle of tribal self-governance and consent remains constitutionally sacrosanct under Articles 244 and the Fifth Schedule.

Forcing “surrender” after 21 years of unresolved tsunami displacement demands ignores these safeguards and exploits vulnerability.

Ongoing legal battles reinforce the illegality: Petitions challenging forest clearances are before the Calcutta High Court, with hearings on FRA compliance and consent issues. Environmental clearances face scrutiny in the National Green Tribunal.

The National Commission for Scheduled Tribes has previously flagged discrepancies in FRA implementation for this project.Snatching ancestral lands via pressure tactics is not development—it is dispossession dressed as progress. It breaches India’s constitutional commitment to protect vulnerable tribes, as articulated in Supreme Court judgments emphasizing tribal autonomy and resource rights.

The administration must halt coercive measures, initiate proper FRA processes with transparent Gram Sabha consultations, and respect the Tribal Council’s refusal. Only then can any project proceed lawfully. Until rights are settled and consent is truly free, the Great Nicobar port’s land grab remains indefensible—and illegal.

The future of the Nicobarese, and India’s credibility on indigenous justice, hangs in the balance.

Naorem Mohen is the Editor of Signpost News. Explore his views and opinion on X: @laimacha.