With an astonishing 303 billion barrels of proven oil reserves—the largest on the planet, dwarfing even Saudi Arabia’s holdings and representing about 17% of the global total—Venezuela should be one of the wealthiest countries imaginable.

Yet, it languishes in economic ruin, its people enduring hardship while superpowers circle like vultures. The reason? It’s not just bad luck or mismanagement alone; it’s the irresistible allure of that underground treasure trove that makes Venezuela a perpetual target for geopolitical maneuvering.

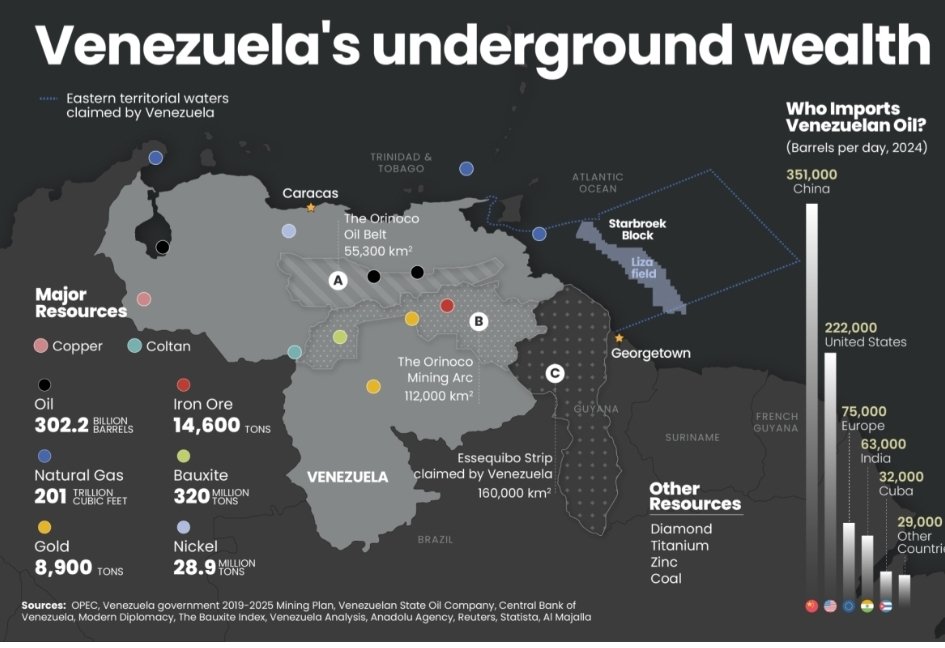

Most of Venezuela’s oil lies in the vast Orinoco Belt, a region rich in heavy crude that, while costlier to extract and refine, could fuel global markets for generations if properly developed. This isn’t light, easy-flowing oil—it’s thick and demanding, requiring advanced technology and massive investment.

But the sheer volume makes it a game-changer: enough to reshape energy security for any nation that controls it.This pattern of foreign covetousness isn’t new—it’s woven into Venezuela’s history.

As early as the 1902–1903 Venezuelan Crisis, European powers Britain, Germany, and Italy imposed a naval blockade, bombarding coastal forts and seizing ships to force repayment of debts, many tied to infrastructure supporting emerging resource exports.

Though oil was just beginning to flow, the incident highlighted how Venezuela’s wealth drew gunboat diplomacy from afar.A century later, in April 2002, a short-lived coup ousted President Hugo Chávez—who had sought greater national control over oil revenues—for 47 hours.

Declassified U.S. documents reveal the CIA had advance knowledge of the plot by dissident military officers, yet did nothing to warn the government. The Bush administration quickly recognized the interim regime, underscoring how threats to foreign oil interests could spark covert backing for regime change.

Decades of underinvestment, corruption, and crippling international sanctions have slashed production to a fraction of its peak—hovering around 800,000 to 1.1 million barrels per day in recent years, compared to over 3 million in better times.

Western companies like Chevron linger in limited operations, but the sector is a shadow of its former self. Venezuela’s tragedy is the classic “resource curse”: immense wealth breeding poverty through mismanagement, while inviting foreign meddling.

And that’s where the superpowers come in. The United States has long viewed Venezuela’s oil as a strategic asset in the Western Hemisphere—close, abundant, and capable of reducing dependence on volatile Middle Eastern supplies.

Recent events highlight this: renewed U.S. pressure on the Maduro regime isn’t purely about democracy or human rights; it’s about securing access to those reserves, potentially flooding markets with friendly oil and countering adversaries.

Russia and China, meanwhile, have entrenched interests through loans and investments, effectively owning stakes in future production as debt repayment. Beijing and Moscow see Venezuela as a foothold in America’s backyard, a way to challenge U.S. dominance in global energy.

Control over Venezuelan oil isn’t just profit—it’s leverage in great-power rivalry, influencing everything from OPEC dynamics to sanctions evasion.Beyond oil, Venezuela boasts vast untapped minerals: gold, iron ore, bauxite, diamonds, coltan (critical for electronics), and more.

These add another layer of temptation, especially as the world hungers for resources in the green energy transition.In my view, the relentless pursuit of Venezuela by superpowers reveals a harsh truth about global affairs: sovereignty often bends to the allure of resources.

While leaders decry interference, the real driver is that black gold beneath the Orinoco. Until Venezuela stabilizes and develops its wealth independently—or until the world moves fully beyond fossil fuels—this nation will remain a chess piece in a larger game.

The pity is that its people, not distant powers, deserve the prosperity that 303 billion barrels could bring.

Naorem Mohen is the Editor of Signpost News. Explore his views and opinion on X: @laimacha.